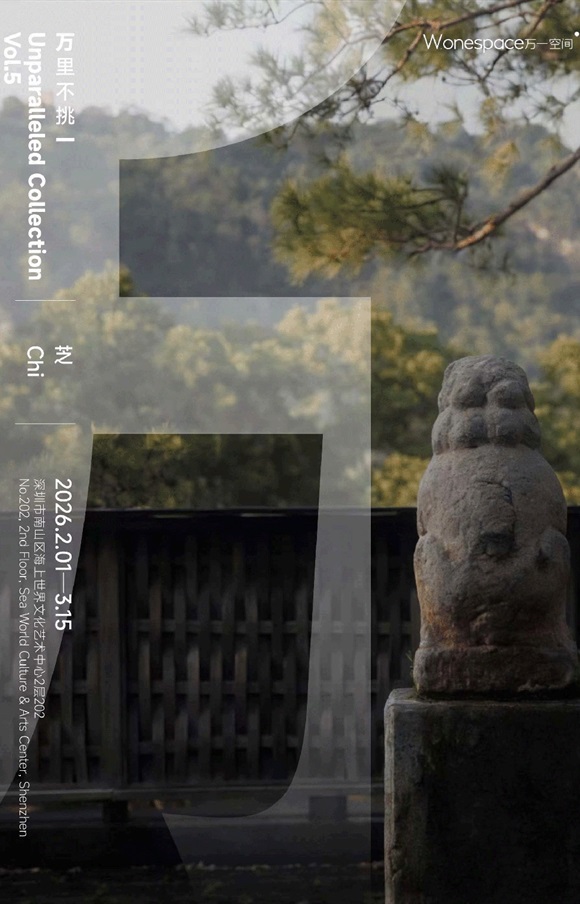

Chi, born in the 1970s, art collector and curator.

For over a decade, Chi has continuously and systematically engaged with both ancient and contemporary art from the perspective of a private collector. Rather than pursuing grand historical narratives, her collecting practice returns to everyday life. Through close attention to objects, utensils and aesthetic details, she reflects on how aesthetics is understood and embodied in Eastern cultural traditions. Since 2018, Huancui Garden Villa and House of beautiful things have served as her spaces for aesthetic practice, through which she proposes and practices an “At Home” vision of contemporary garden living.

In 2019, Chi founded the lifestyle and object brand V-LIFE. Centered on making and spatial practice, the brand focuses on the locality of materials and objects, exploring the contemporary application and extension of Song dynasty ceramics and other traditional materials in daily life. Through this exploration, it seeks to reconstruct, within today’s cultural context, the profound relationship between objects, materials, craftsmanship, and everyday living as an Eastern mode of expression.

Between 2021 and 2025, Chi curated and presented more than 10 exhibitions addressing objects, craftsmanship, and the aesthetics of life. These include Chinese Ceramics in Black and White; Hundreds of Bamboo Crafts Art Exhibition; Fine Stone Tools in Chinese Art; Art, Myth and Ritual: An Appreciation of Neolithic Pottery from Ancient China; Silent at This Moment: Chinese Song Dynasty Chinese Ceramics in Dialogue with Qiu’s Photography and Echo of The North: The Living Tradition of Cizhou Ware.

Moreover, Chi has been deeply engaged in culinary and spatial aesthetic practices, from the adaptive reuse of the century-old building Yong to the exploration of new expressions of traditional materials. By bringing art, exhibitions, Song dynasty ceramics, and garden elements into the dining space, she creates encounters between cuisine, objects, art, and diners. Through this holistic approach, Yong has been awarded one Michelin star in Guangzhou for three consecutive years, as well as the Michelin Green Star for two consecutive years.

Currently, Chi is preparing a new art space, Yong Gallery, scheduled to open in March 2027 in the Greater Bay Area. Through exhibitions, collecting, spatial practice, and the articulation of objects, the gallery will continue to foster dialogues between contemporary and traditional art, raising questions about life and beauty.

What Chi advocates is a form of “spatial aesthetics” rooted in tradition yet oriented toward the present. In her understanding, space is not a neutral container but a totality jointly constructed by objects, materials, light, and the paths of viewing and movement. Strategies drawn from traditional Chinese garden design—such as winding routes, concealment, view borrowing—are introduced into the spatial structure. Through the arrangement of objects, screens, paintings and installations, viewers are prompted to continually adjust their sightlines and rhythm as they walk, producing an experience of changing views with each step. This spatial approach does not seek instant visual impact. Conversely, it aligns with the slow, unfolding process of perception embedded in everyday life.

In selecting objects, Chi focuses on the sense of time inherent in traditional crafts and materials themselves: the roughness of clay, the warmth of glaze, the wear of wood, the traces of age in fabric. These marks of time are neither concealed nor polished away; instead, they become the key through which objects connect with contemporary life. By situating them within modern contexts of living and display, Chi repeatedly returns to a fundamental question: how can traditional materials and crafts continue to participate in life today?

The emergence of V-LIFE represents Chi’s practical exploration of this question.“Tradition” functions as a medium that remains creatively active in the present, as opposed to being a fixed moment in history. By re-examining the physical properties of materials and the logic of traditional techniques, by placing them within contemporary modes of living, she seeks to initiate a transformation from “the ancient” to “the present”. This is not a reproduction of traditional forms, but a process that begins with traditional materials and responds to contemporary spatial scales, lifestyles, and aesthetic experiences. In this process, traditional craftsmanship is no longer merely something to be “preserved”; through use, it completes its transformation from historical legacy to contemporary practice, allowing the idea of “making the past serve the present” to be an ongoing act of creation.

Far from being driven by objects or artworks on their own, this exhibition offers a reconstruction of everyday living scenarios. Contemporary art, ancient objects, furniture, lighting, and other elements are no longer distinguished by hierarchies of value or by temporal divisions. Alternatively, they coexist within a space that is actively lived and experienced, merging and responding to one another to form a relaxed yet internally coherent order.

Within Chi’s collecting practice, space is not the result of being filled, but a process of continual leaving open, adjustment and perception. Through this exhibition, we are invited to enter that process itself—to observe how objects find their place in time and in life, reconsider how “art” and the “everyday” can exist in a state of mutual coordination.

For over a decade, Chi has continuously and systematically engaged with both ancient and contemporary art from the perspective of a private collector. Rather than pursuing grand historical narratives, her collecting practice returns to everyday life. Through close attention to objects, utensils and aesthetic details, she reflects on how aesthetics is understood and embodied in Eastern cultural traditions. Since 2018, Huancui Garden Villa and House of beautiful things have served as her spaces for aesthetic practice, through which she proposes and practices an “At Home” vision of contemporary garden living.

In 2019, Chi founded the lifestyle and object brand V-LIFE. Centered on making and spatial practice, the brand focuses on the locality of materials and objects, exploring the contemporary application and extension of Song dynasty ceramics and other traditional materials in daily life. Through this exploration, it seeks to reconstruct, within today’s cultural context, the profound relationship between objects, materials, craftsmanship, and everyday living as an Eastern mode of expression.

Between 2021 and 2025, Chi curated and presented more than 10 exhibitions addressing objects, craftsmanship, and the aesthetics of life. These include Chinese Ceramics in Black and White; Hundreds of Bamboo Crafts Art Exhibition; Fine Stone Tools in Chinese Art; Art, Myth and Ritual: An Appreciation of Neolithic Pottery from Ancient China; Silent at This Moment: Chinese Song Dynasty Chinese Ceramics in Dialogue with Qiu’s Photography and Echo of The North: The Living Tradition of Cizhou Ware.

Moreover, Chi has been deeply engaged in culinary and spatial aesthetic practices, from the adaptive reuse of the century-old building Yong to the exploration of new expressions of traditional materials. By bringing art, exhibitions, Song dynasty ceramics, and garden elements into the dining space, she creates encounters between cuisine, objects, art, and diners. Through this holistic approach, Yong has been awarded one Michelin star in Guangzhou for three consecutive years, as well as the Michelin Green Star for two consecutive years.

Currently, Chi is preparing a new art space, Yong Gallery, scheduled to open in March 2027 in the Greater Bay Area. Through exhibitions, collecting, spatial practice, and the articulation of objects, the gallery will continue to foster dialogues between contemporary and traditional art, raising questions about life and beauty.

What Chi advocates is a form of “spatial aesthetics” rooted in tradition yet oriented toward the present. In her understanding, space is not a neutral container but a totality jointly constructed by objects, materials, light, and the paths of viewing and movement. Strategies drawn from traditional Chinese garden design—such as winding routes, concealment, view borrowing—are introduced into the spatial structure. Through the arrangement of objects, screens, paintings and installations, viewers are prompted to continually adjust their sightlines and rhythm as they walk, producing an experience of changing views with each step. This spatial approach does not seek instant visual impact. Conversely, it aligns with the slow, unfolding process of perception embedded in everyday life.

In selecting objects, Chi focuses on the sense of time inherent in traditional crafts and materials themselves: the roughness of clay, the warmth of glaze, the wear of wood, the traces of age in fabric. These marks of time are neither concealed nor polished away; instead, they become the key through which objects connect with contemporary life. By situating them within modern contexts of living and display, Chi repeatedly returns to a fundamental question: how can traditional materials and crafts continue to participate in life today?

The emergence of V-LIFE represents Chi’s practical exploration of this question.“Tradition” functions as a medium that remains creatively active in the present, as opposed to being a fixed moment in history. By re-examining the physical properties of materials and the logic of traditional techniques, by placing them within contemporary modes of living, she seeks to initiate a transformation from “the ancient” to “the present”. This is not a reproduction of traditional forms, but a process that begins with traditional materials and responds to contemporary spatial scales, lifestyles, and aesthetic experiences. In this process, traditional craftsmanship is no longer merely something to be “preserved”; through use, it completes its transformation from historical legacy to contemporary practice, allowing the idea of “making the past serve the present” to be an ongoing act of creation.

Far from being driven by objects or artworks on their own, this exhibition offers a reconstruction of everyday living scenarios. Contemporary art, ancient objects, furniture, lighting, and other elements are no longer distinguished by hierarchies of value or by temporal divisions. Alternatively, they coexist within a space that is actively lived and experienced, merging and responding to one another to form a relaxed yet internally coherent order.

Within Chi’s collecting practice, space is not the result of being filled, but a process of continual leaving open, adjustment and perception. Through this exhibition, we are invited to enter that process itself—to observe how objects find their place in time and in life, reconsider how “art” and the “everyday” can exist in a state of mutual coordination.